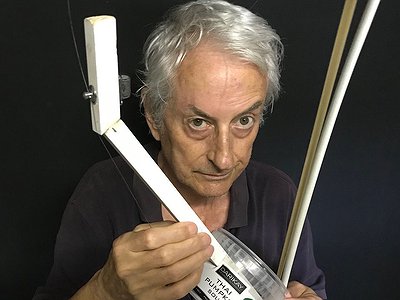

Name: Jon Rose

Nationality: Australian

Occupation: Violinist, composer, improviser, multi-media artist, writer.

Current Release: Jon Rose has a new double album out now on ReR entitled ‘State of Play’. Buy it and find out what the hell he’s talking about.

Recommendation: ‘The Hard Light of Day’ by Rod Moss - an extraordinary book by a visual artist on indigenous relations in a settler society.

‘H is for Hawke’ by Helen Macdonald - in a time of loss, environmental collapse, and the demise of human exceptionalism, this book is a very moving account of interspecies relationships.

And here is another one!

‘Is Birdsong Music: Outback encounters with an Australian Songbird’ by Hollis Taylor - the musical culture of another species (it’s written by my partner, so I confess to an expression of interest).

If you enjoyed this interview with Jon Rose and would like to find out more about his work, visit his official website.

When did you start composing - and what or who were your early passions and influences? What was it about music and/or sound that drew you to it?

At the age of seven I won a scholarship to a music school in England, studying and performing voice with violin as my main instrument. At the age of fifteen I gave up formal pedagogy (it was 1966) because I wanted to improvise and the only thing I could do on the violin was read music. So my first improvising instrument was the double bass - they had one at the school but no one available to play it in the school jazz group - so I put my hand up for that.

In my early twenties I came back to the violin and un-taught myself, learning to play by ear and respond to the physicality of the instrument. At the same time, being a kind of polymath, I was involved in a lot of other creative activities - none of them made much sense - including a job as recording engineer at the Royal Academy of Music, London.

At twenty five, the penny dropped as to what I should do with the rest of my life. It was to create a gesamtkunstwerk around the violin - every imaginable one, with, and about the instrument. I’ve been basically busy with that, and its logical extensions, ever since.

For most artists, originality is preceded by a phase of learning and, often, emulating others. What was this like for you: How would you describe your own development as an artist and the transition towards your own voice?

The models for improvising on the violin did not interest me at all - they all sounded a bit cheesy - so I had to make my own way without much help. I went back to basics - how to put rhythm in the bow, how to play in any tonality including 12 tone rows, how to put intelligence and independence into the left hand.

I thought that a whole smorgasbord of styles would be the basis of a meta-style - being able to deal with any sonic situation that might present itself whether playing in an Italian club, a C&W band, a supermarket, a free way, a desert, a jazz club, a factory, the sea, a pneumatic drill - any sonic situation I could take a violin.

How do you feel your sense of identity influences your creativity?

My post war generation are basically a rootless bunch. I have many identities but possibly my main character has been developed as an immigrant, having lived and worked in many countries over my career. Where I was born seems quite irrelevant to how my life has progressed. ‘Ich hab’ noch einen Koffer in Berlin’ about sums it up, but right now I’m living in Alice Springs in the middle of Australia.

My genetic history has English, Afghan, Persian, and French contributions - my mother’s family name was Khan. In the end it’s all species nonsense, you start with what you’ve given and make the best of it. Being just one person, I created my own dynasty of violinists - The Rosenbergs.

What were your main creative challenges in the beginning and how have they changed over time?

I’ve already touched on that. Sorting out how to use my various skills took about ten years. Once I made the violin central to the career trajectory, everything fell into place, no matter how ‘far out’ I explored.

There are many aspects of my life that in retrospect appear cyclic. Projects that I undertook as a kid and later as a young man, come around and around in different guises. For example, in the 1960s, I used to make my own fictional radio pieces on my brother’s tape recorder, then later professionally I had a whole side career as a radiophonic artist giving my fantasy full reign, making over 40 major productions for radio stations all over the world. From that work developed many multi media projects. So I would start with an idea that would eventually have a multiplicity of outcomes - music, performance, radio, film, installation, book (the ‘Violin Music in the Age of Shopping’ is a good example of this way of working.)

I would say that just when you think you have exhausted the options or propositions on some particular notion or idea, something else pops up.

Time is a variable only seldomly discussed within the context of contemporary composition. Can you tell me a bit about your perspective on time in relation to a composition and what role it plays in your work?

Composition is an artificial time warp, useful sometimes in that the composer has time to consider, to research, to adjust, to change his mind. In the moment of improvisation, none of that is particularly relevant, you have just the time the music takes.

I once had a solo violin gig in a gallery in Hanover - playing a free improvisation. As I looked down at the feet of the front row I saw that everyone was tapping their foot …but all in a different ‘time’ to each other. They were all listening to the same music unfold but their experience of it was entirely other.

As I write this I am sitting beside ten violin clocks which I have had in my museum collection of violin artefacts for over 30 years (The Rosenberg Museum). The clocks are all ticking away, marking time, and they are all set to a different time zone on their dials. Our species constructs such illusions, illusions to make sense of our predicament, time is one of them. Death though is real.

How do you see the relationship between the 'sound' aspects of music and the 'composition' aspects? How do you work with sound and timbre to meet certain production ideas and in which way can certain sounds already take on compositional qualities?

Outside of pure improvisation with no agenda, I tend to envisage music in terms of projects or a collection of sonic material or newly made instruments (also improvisations although I keep a notebook of drawings and construction scenarios). Composition (despite the aleatoric flirtations of the 1960s) tends to end with a fixed result which doesn’t interest me. Most of my material can be re-worked or re-discovered, I see a ‘composition’ as music temporarily paused to be re-examined at a later date.

Sound itself can be analysed for its structure but I find that relatively uninteresting (although sometimes necessary), I want sound to have agency that leaves you breathless - transformed.

Collaborations can take on many forms. What role do they play in your approach and what are your preferred ways of engaging with other creatives?

Mostly I prefer the simple process of improvising with other musicians who are on the same wave length. It’s stress free. Large scale projects demand other strategies. At 70 years old, I’m really over community projects where you do all the work, with help from a couple of sympathetic creators, and then the community turns up when all the work is done … ready to party. Screw that.

My last community project was in 2013. The Pursuit project (a self built mobile bicycle powered orchestra of 130 machines) nearly killed me. But I’m happy to transfer knowledge when appropriate - my wife and I continue to contribute to an indigenous school in the Kimberley (Warmun).

Take us through a day in your life, from a possible morning routine through to your work, please. Do you have a fixed schedule? How do music and other aspects of your life feed back into each other - do you separate them or instead try to make them blend seamlessly?

In my younger and less cancer restricted days, I was capable of managing multiple projects simultaneously while touring at the same time. Now I tend to work only on a fewer things over a week. I have no problem stopping an activity and wandering off into the garden to admire the rocks (huge things).

Concert touring is no longer viable and so I work at home. A typical day may have some violin practice, some instrument making, some commissions to take care of (in front of a computer). I have left the digital interactive investigations in a metaphorical box marked ‘repertoire’ - I have all previous projects saved on retired Macintosh computers, they still work, and I have no desire to continuously update to satisfy the capitalists at Apple. When the machines finally break, then that’s the end of that particular project (eg. The Hyperstring Project).

Most important for me is that I arrive at the end of the day having created or learnt something that adds to my experience of life.