What are currently your main artistic challenges?

I have a permanent challenge that is to make alive, enjoyable music. We are in a moment of over information and fetishism. We can have a strong tendency to fit too well in the specific boxes people are divided in. Or in one box, or to fit in several boxes in order to find work. I think that our lives are more vast and beautiful than those boxes and that it does not fit really in any of them. To do alive music means to be a bit aware of what is going on, to listen and observe society and what other artists do, but mainly to work and enjoy offering in music what is honestly my own life. And that does not come checking this and that but through my own existence.

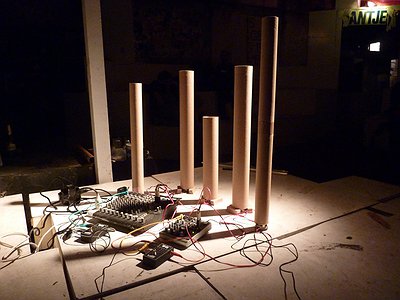

In concrete terms I am presenting live, the music that I composed for Zero plus Zero, a one hour piece played with soprano saxophone, bass clarinet, preparations, analog electronic devices and Sruti Box. I'm also presenting pieces related to the perception experience. I am using wireless speakers that fly hanging from big balloons filled with Helium, placing Tunebugs in objects in the room, or cardboard boxes, recording familiar spaces placing the microphone inside cardboard tubes of differing dimensions (that gives different pitches, in a natural way, to the field recordings).

I work decomposing the harmonic spectrum of the pitches and check how the different frequencies travel in the space, or how they resonate in different objects in the room. I am fascinated with this. And I can say that working with these devices is beautiful itself, but it is also making me play my usual instruments in a different way. I think of improvisation not only as decisions that I have to take regarding the other musicians, but also and mainly regarding the space, and the social life around me.

I’m doing this work mainly in solo. It interests me and has not very much margin for improvisation, but I do it anyway, and enjoy doing collaborations with other musicians. But it is difficult these days to find time to work together with other people in the way I wish to do that. Musicians have many projects, and I have my family life that makes my time to meet people more tight . So I do it as much as I find it possible. I work alone quite a lot. And this is certainly a challenge after having worked in a dynamic environment that made me more than anything meet and work with other musicians. But I feel also that is a natural tendency, that I’m enjoying a lot.

What do improvisation and composition mean to you and what, to you, are their respective merits?

I think that the idea of improvisation and composition as different disciplines is obsolete. Not the practise of composing in real or not real time, but the separation of these practises as a way to achieve this or that. Neither the fact of deciding to improvise makes the music more fresh, nor deciding to compose makes it more solid. It is a personal choice. What we do before, during or after going on stage, or doing a record, is a personal choice and is up to us to have the talent to achieve satisfying results. There are other aspects of the music practise like density, activity, placement, projection, degree of gesture, expression and weight that are much more crucial to me than if the music is composed or not in real time. Some years ago, I thought that an important aspect of improvising is that each musician can offer material totally personal in a very evident and immediate way. I tend to relativise the importance of this aspect now, probably just because I’m more interested or just as interested in other aspects of music, as I was in material.

How important are practising and instrumental technique for achieving your musical goals?

I think that is very important to spend time with the devices that you enjoy. Not to be crazy about it. To have a real, good life is more important than anything. But in order to find your life in what you do, to find yourself in your instrument I think that it's nice to spend time with it. If it is a regular traditional instrument it's important that a teacher transmits to the student a good technique. The right way to achieve sound, how not to injure your body, how to enjoy playing relaxed and produce good sound. A teacher, a real master, can be totally illuminating. But it's important to know that the deep musical work is personal, alone or with other musicians, but personal. It depends totally and only on you. On your curiosity and tenacity to go beyond many moments of weakness, that appear in different ways. And that there are many ways of learning, that do not come only through a teacher. Listening to good music, attending to shows, sharing music with others…By the other way, many modern or non traditional musical devices are impossible to learn, and many musicians did not learn with anybody and sound great. To learn can be problematic, it can impose on the musician lots of problems. I think that is usually the case.

In the case of the instruments that I play I have a certain basic discipline, that gives me a basic shape to do what I want to do.

How do you see the relationship between sound, space and performance?

I think that it is fundamental. Sound is a living creature and it’s three moments have to be considered as fundamental in the life of this creature: The way the vibration is produced, the way it travels (space) and the way it’s perceived, listened. In the actual situation, our spaces are being constantly besieged by the market logic, as well as the way our bodies have to behave in them. The impact of amplification has been very negative in that sense, in everyday life and in the massive practise of music.

In the first aspect just imagine your city, your public shared life without having unwanted music, so loud, so often. In terms of performing it can be interesting to think how did musicians live with the lack of amplification for centuries and what good musical results they achieved. Renaissance musicians for example, if you check the scores, and the places where they performed their music, how they created music FOR them, you will see that they had a deep sense of space, after centuries of working in an acoustic way. Traditional musicians from India, Bali or Africa are incredible in this sense. People singing in a football stadium in Argentina or Brazil look to me as if they have a wider dimension of that space than the musicians or sound engineers, who amplify bands in a flat way, using amplification as a military weapon almost. In those huge stadiums where it's impossible to listen properly and all you can do is watch their untouchable figures in gigantic screens. Amplification makes some people put an acoustic guitar with a drum set at the same level of intensity, with no consideration to the origin and the characteristics of the instruments. I think that is anti-natural and strange. I’m not of course against the use of amplification, I love electronic music. I mean in massive social terms. Some people manage to do good work with amplification systems pushing them to their extreme. Mika Vainio, Kevin Drumm, Sunn 0))) , Maryanne Amacher have done amazing work combining amplification, perception of sound and the space.

People working with acousmatic diffusion and a handcrafted approach to speaker construction have a lot to offer. The problem is that very often they are restricted to specific institutions and the few people connected to them, or that the devices are just too expensive.

I think that is fundamental, for our work as musicians, and for society to develop an understanding, to think and experience the space, and how the sound inhabits it. To be agents of spatial liberation and proper listening. Many things can be done with basic technology if we develop an intense sense of space. Alvin Lucier has done, in my opinion, some of the most astonishing and beautiful work regarding sound in the space, and in many cases it was with very basic technology. It was his creativity, his sense of the space and understanding of the sound phenomenon, that created those marvellous pieces, and not the technology.

I listened once to Steve Lacy playing live, and I could perceive how the work with the harmonic spectrum that he did with his soprano saxophone made it sound so rich in the space, and it was just him and his instrument, working in the proper direction.

In my personal experience, to play with Radu Malfatti has been wonderful. To experience that playing as quiet as possible you can reach any corner of the room, appealing to the listeners ears. To play inviting people’s ears, to enjoy the room and work together with it. To learn to chose frequencies, which ones are more directional, which ones hug the audience. How to deal with the environmental noise. I have mentioned previously more technically specific experiences that I am doing regarding sound in the space. It is for me a deep experience to work with sound thinking of it from the beginning as a living creature that exists in the space, I try at the moment to live it in an intense, sensual and intelligent way in my music. And try to think of it as a liberation agent of the space and the time that we share.

Derek Bailey defined improvising as the search for material which is endlessly transformable. Regardless of whether or not you agree with his perspective, what kind of materials have turned out to be particularly transformable and stimulating for you?

Derek Bailey has written and offered so much and so deeply about improvisation. There are many aspects that we can quote and analyse from his texts. I think that any sound is transformable. I cannot say endlessly but in a huge dimension. Even the exact same sound placed in a different spot in time, is already very different. I think that improvisation, and any music, works with material (the space as part of it), but also with structure, form and expression as main aspects. The privilege to material that Bailey mentions in this quote shows a certain approach to improvisation. That makes form and structure somehow depend on the development of the material. I used to think that material had a privilege on the other aspects in improvisation several years ago. Even that if I was interested in form and structure I should compose. I try to focus more on the structure and form now. It makes it necessary probably to establish a basic agreement about the way we will improvise, while Bailey´s approach was certainly more free. By the other way, you can improvise with very limited material, and then the most tiny alterations of it that you make will become more listenable. I work in this way. Asking the ear for special attention to those micro movements.

Purportedly, John Stevens of the Spontaneous Music Ensemble had two basic rules to playing in his ensemble: (1) If you can't hear another musician, you're playing too loud, and (2) if the music you're producing doesn't regularly relate to what you're hearing others create, why be in the group. What's your perspective on this statement and how, more generally, does playing in a group compare to a solo situation?

I agree with the basic idea of listening to the other musicians carefully. It is certainly a crucial step compared to the tendency to centre the music in your own production. But sometimes it's ok to play louder than the other, or quieter, not all the time. The established idea of everybody playing balanced all the time, makes music sound flat, too often. Personally I like it when that happens but in a subtle way, when the sounds cover and disappear into each other in a subtle way. I love when this happens, and find it fundamental.

The main aspect, I think, is a matter of presence. Usually to play louder too often and to be more present than the others goes against the music. That can happen if you play too active, or expose ideas that have more to do with exposing yourself than putting them at the service of doing good music. Sometimes a non strictly musical decision, but a gesture, or a subtle use of an object can offer a dynamic to the set without having to play louder or adding a dramatic expression to the set. I enjoy doing this.

Regarding the second aspect. I think that is fundamental if you play with people to think the music as a collective production, that means to relate . But the ways we relate should not be the most obvious, It can be boring to play in a very responsive way. To oppose, to disappear, to ignore, to cover the other one can be very interesting. The basic situation, is to be aware of the others' presence at any moment and to decide actually, more than anything, how much we want to relate playing and listening. To stop listening and to stop relating for a while, as a way to create tension and go deeper into the interaction itself can help to produce dynamism and make the music very alive, even if these movements happen in ways that are not easy to perceive in an evident way.

Interviews / About

Fifteen Questions Interview with Lucio Capece

Giving the sound back to the space

Unticking the boxes

We are in a moment of over information and fetishism.