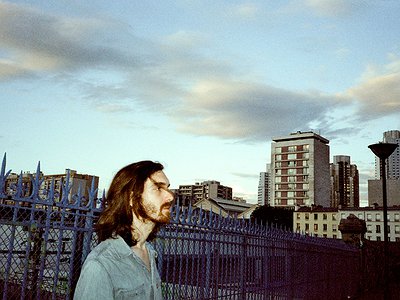

Name: Renaud Bajeux

Nationality: French

Occupation: Musician and sound engineer

Current Release: Magnetic Voices From The Unseen on Nahal Recordings

Recommendations: The Drought by Puce Mary / Julien Gracq, Le Rivage des Syrtes

When did you start writing/producing music - and what or who were your early passions and influences? What is it about music and/or sound that drew you to it?

I started composing pretty late, around 30, after a long period of inhibition. When I was a teenager, in the 90’s, I was strongly into classical music, as I was learning cello and discovering the repertoire of this instrument as well as some chamber and orchestral works, and feeling strong emotions facing Bach, Chopin, Shostakovich etc. But at the same time, I was fascinated by artists like Portishead, Eels, Ez3chiel, Amon Tobin for whom sonic singularity is primordial.

I grew up with this kind of schizophrenia between conservative and weird sounds without being able to make a real synthesis with my cello, except for some random attempts which didn't seem like real music to me but may have looked like bad improvised music (which I had no clue existed at the time).

Later on, as I decided to become a sound engineer. I discovered French electroacoustic music with Parmegiani, Henry and Ferrari etc... and directors like Tarkovski, Malik, as well as Dumont and the Dardennes Brothers. Both discoveries drew me to another aspect of sound. Electroacoustic music gives a chance to any sound to be a music material, and movies to work with real sounds as a poetic, sensitive and emotional vector.

I realized that I had always felt confined by the harmonic and rhythmical grids used in most music, classical or not. Not that I didn’t like it as a listener, but I wanted to explore further, to build a sonic voyage. More than songs, I wanted to give a shape to a sonic daydream where reality, sensation, intimacy and fantasy merged, just as when we stay with our coffee at a terrace, listening to the cars passing, the voices and footsteps, our thoughts and imagination floating around.

For most artists, originality is first preceded by a phase of learning and, often, emulating others. How would you describe your own development as an artist and the transition towards your own voice? What is the relationship between copying, learning and your own creativity?

I always remember having some sound imagination, inner visions, in my mind that I wanted to put outside myself.

First, it took me a long travel to discover what shape it would wear, listening to a lot of music.

On the other hand, the most difficult thing for me was – to quote Henri Bauchau, a Belgian writer that helped me a lot – to overcome the inner resistance. Meaning for me: all the inhibition and low self-esteem that make any of your productions smashed by your own judgment without letting any chance for your emotions to find their way through.

The classical music studies, their seriousness, their narrow-mindedness and the figure of the mighty Composer whose genius can't be equaled paralyzed me. I am not the only one, considering how so little classical instrumentalists make their own music. It is a long process to free us from the cultural authority and find some artistic legitimacy to do what we feel right to do.

It took me time to be respectful with my sonic emotions, to consider them as an unalienable basis for my music whatever other people might say.

Working with sounds as a sound designer was also an extraordinary school, to work with unshaped multilayered sounds to build an organic soundscape, sculpting, structuring and guiding a confused matter more than applying a transcendental intention to an obedient instrument.

What were your main compositional- and production-challenges in the beginning and how have they changed over time?

For my first project (Magnetic Voices from the Unseen), I needed to find a singular sound matter that could free me from “déjà vu” and be my own playground.

As a friend told me about the coils converting the electromagnetic field to sound, I dived deep into it, fascinated by the richness of this soundscape and its duality both harsh and harmonious, which moved me particularly. I decided, as a composing rule to use exclusively this sound and to not use any sound transformation other than filtering and transposition, so I could keep their own identity, deciding only which spectral part I wanted to highlight in it.

Another challenge was to build a living soundscape, just as if I was wandering into this inaudible soundscape from a place to another. I used the two coils just like a boom with a mike or a paintbrush, being able to translate, oscillate, travel around the magnetic field.

What was your first studio like? How and for what reasons has your set-up evolved over the years and what are currently some of the most important pieces of gear for you?

My first studio was my bedroom; it is still the case in an expensive city like Paris. I had basically a sound card, a computer and three speakers I used for cinema sound editing.

My first project Magnetic Voices from the Unseen involved only two electromagnetic coils that cost 1€ each. That's it. I recorded hours of rushes of magnetic radiations from different devices, then I just used my workstation to edit and mix it with some software EQ and reverberation.

Recently I started using modular synthesizers. I built my own Eurorack system and I am currently working on a new project involving exclusively the Serge System of the INA-GRM. Once again, for this project I recorded hours of “rushes” that I am currently editing.

If I had to list the 3 most important pieces of gear I ever used it would probably be :

1. the Serge Wilson Analog Delay I used at the INA-GRM.

2. My Eurorack System, particularly the Resonant Eq & Wave Multipliers by Random Source and Tapographic Delay by Matthias Puech & 4MS.

3. My OTO Biscuit, which is the first and only “effect” I have and which I use for my live performances.

How do you make use of technology? In terms of the feedback mechanism between technology and creativity, what do humans excel at, what do machines excel at?

I try to use the machines in a way that surprises me. That's why I’d rather use complex systems like modular rather than pedals or other effects. I like to create self-evolving sounds that are interesting in themselves rather than predictable ones. It was already what I was looking to use electromagnetic coils with the own living magnetic life of the devices I recorded. I try to build complex soundscapes rather than clean separates tracks. I am often disappointed and bored by sound that is overdetermined and fixed.

In this way, the tools are really important because if we program the unpredictable they need to be open and versatile to give us a large playground to explore.

I tried in the past to work with software like Max-MSP or Pure Data which are cheap tools made awesome by the hard programming time you spend on it, but I came to hardware synthesizers because I was more interested in the instrumental side than the pure programming one. Programming for months before making real music made me lose the spontaneity and the emotion during the process.

Production tools, from instruments to complex software environments, contribute to the compositional process. How does this manifest itself in your work? Can you describe the co-authorship between yourself and your tools?

With hardware modular, effects etc., the difficulty is: on the first hand, I have to find the same relationship as with an instrument (my cello). My hands and my fingers need to be a extension of my ears. That instinctive way allows you to make live performance while really playing with your tools. Then, turning a knob expresses a feeling, has a musical function more complex and expressive than “I shift the frequency of the filter”, “I increase the amount of the LFO”. Sometimes I like to patch some cables just to try, without knowing exactly what will be the result and try in a short time different configurations until I find something interesting that I couldn't have imagined.

On the other hand, these tools, modular in particular, have an important conceptual, technical background. If you want to be free in the way you use them, you need to understand precisely what the input, outputs and the knobs actually do, and how it will react if you give them something else than they are originally waiting for (trigger instead of audio, audio instead of envelope, etc...). Not because you won't be able to use them otherwise, but because a lot of modules are a lot more than you can imagine and if you allow yourself some time to think about it, you can hijack them.

For example, the Wilson Analog Delay can be at first understood as a vintage delay, but in fact it can produce something sounding like a distorted guitar if you patch it a certain way, or give you some amazing harmonic sweeps you won't expect at first.

Collaborations can take on many forms. What role do they play in your approach and what are your preferred ways of engaging with other creatives through, for example, file sharing, jamming or just talking about ideas?

As of now I have mostly made music alone, because I needed to find my own voice before working with someone else.

One thing I do that I inherited from the movie's workflow, is that I often ask for some feedback from my friends or of course my label NAHAL Recordings. As music is made for others, I find it really important to know what people feel listening to it. I know it could be confusing also, but as I generally know pretty well what I want to do, I try to find the right balance between the feedbacks and my vision.