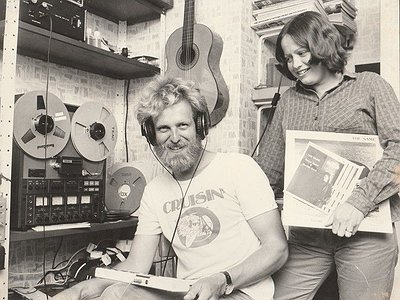

Name: Robert Cox

Nationality: British

Occupation: Composer, improviser, musician

Current release: The Same's 1981 album Sync or Swim is being reissued 40 years after its initial release via Freedom To Spend.

Recommendations: "Les Elemens" composed by Jean-Fery Rebel in 1737. Acclaimed by some as the piece of music that marked the end of the Baroque Age.

"A Pure Solar World, Sun Ra and the birth of Afrofuturism" by Paul Youngquist.

A book that accomplishes the seemingly impossible task of chronicling Sun Ra’s life and giving context to his work with The Arkestra.

If you enjoyed this interview with Robert Cox, visit the official Rimarimba website for a deeper look into his work.

When did you start writing/producing music - and what or who were your early passions and influences? What was it about music and/or sound that drew you to it?

I taught myself classical guitar as a teenager but found it was not a particularly satisfying experience. Hearing John Fahey and Leo Kottke made me realise steel strung guitar offered many other possibilities which were much more interesting to me. At around the same time, electronics classes at school sparked a lifelong interest in building devices to make or mutate music and noise.

Music seems to me to be the most ephemeral and malleable of the arts; from silence to the gigantic soundscapes of Messiaen’s Turangalila Symphony, the stately unfolding of John Fahey’s On The Sunny Side Of The Ocean or the cool and swinging perfection of Bill Evans’ Live At The Village Vanguard. When the music stops - the impression left in the listener’s mind is what? Something much less tangible than an image of a statue or painting or actors on a stage; I have always found that intriguing.

A mere wash of keyboard texture can evoke happiness, desolation, a feeling of unease. All this, of course, because we listen with our memories. Writing, recording, listening are a continuous process of refining and redefining memory.

For most artists, originality is preceded by a phase of learning and, often, emulating others. What was this like for you: How would you describe your own development as an artist and the transition towards your own voice?

Arriving from a classical guitarist’s start I was not aware of open tunings! Consequently, my attempts to sound like Fahey or Kottke were doomed to failure. I also found syncopation difficult on solo guitar, but lines tumbling over each other relatively easy to achieve on a tape recorder or two or three.

At about the time I was beginning to make headway with multitracking guitar parts I discovered Terry Riley. 50 years later I am still trying to fuse the music of Fahey, Riley and Captain Beefheart into something coherently and recognisably mine.

How do you feel your sense of identity influences your creativity?

My paternal grandfather was a stonemason, my father a farmer and then a builder and I, too, have been a self-employed builder. A solitary life of making things runs in the family. I have always wanted to know and see how things work. A rack of sound processors and synthesizers are much more satisfying to work with than composing software on a computer.Opening up and modifying devices is an inherent part of music production for me.

What were your main creative challenges in the beginning and how have they changed over time?

Lack of money was the biggest challenge. I have acquired more disposable income over the years and technology has become, relatively, much cheaper. It is much easier to work with a 32-track recorder, racks of synthesizers and processors and an indecent number of guitars than it was with failing valve-powered tape recorders, a couple of cheap guitars and some homemade devices.

It is, of course, much harder to chart a creative course when the studio offers so many possibilities to add another layer of guitars, bring the bass forward a bit, reposition that synthesizer in the mix and so forth.

As creative goals and technical abilities change, so does the need for different tools of expression, be it instruments, software tools or recording equipment. Can you describe this path for you, starting from your first studio/first instrument? What motivated some of the choices you made in terms of instruments/tools/equipment over the years?

My first tape recorder was a Sony TC377 open reel two track. I discovered the inputs and outputs could be cross-connected left to right and, with a WEM Copicat in the loop, produce long Riley-like delays. Multitracking became possible with the addition of a homemade mixer and two old Ferrograph recorders. Later, A TEAC A3440 enabled much easier multitracking. A Yamaha CX5M music computer and MIDI in general appeared to offer the perfect execution of my compositions but were, in retrospect, a blind alley. Too much perfection, too little humanity.

Nowadays a Roland MV8800 is employed only as a programmed percussion generator. I multitrack real guitars, a MIDI guitar and a MIDI keyboard to build up compositions, sometimes in short loops, sometimes in longer flowing lines.

Have there been technologies or instruments which have profoundly changed or even questioned the way you make music?

The Yamaha CX5M and a brief dalliance with Sibelius software were enough to convince me I need to play my music rather than just program it.

Not being particularly proficient on any instrument has caused me to split my compositions into small and easy to play fragments. If I have a recognisable sound it is in great part a result of technical limitations.

Collaborations can take on many forms. What role do they play in your approach and what are your preferred ways of engaging with other creatives through, for example, file sharing, jamming or just talking about ideas?

Apart from The Same project and a few pre-taped contributions to Rimarimba: In The Woods, I have worked, and continue to work, on my own in the studio. Having said that, the Rimarimba Scratch Orchestra that came together for one improvisational gig early in 2020 was great fun and is something I would like to do again.

Take us through a day in your life, from a possible morning routine through to your work, please. Do you have a fixed schedule? How do music and other aspects of your life feed back into each other - do you separate them or instead try to make them blend seamlessly?

Mornings always start with muesli, fruit, nuts and yoghurt and have done for all of my adult life. An ever-increasing number of mugs of coffee then propel me through reading the news and answering emails. My wife, Viv, and I run a large allotment where we grow a lot of our own vegetables and fruit. We are there for at least a couple of hours on most days.

I spend a lot more time listening to, and thinking about, music than actually working in the studio. Projects take shape in my head and are then executed in intensive bursts every few months or so. I do try to find some time to play acoustic guitar fairly often and always feel guilty about my limited technical abilities.

Can you talk about a breakthrough work, event or performance in your career? Why does it feel special to you? When, why and how did you start working on it, what were some of the motivations and ideas behind it?

The Same: Sync Or Swim, obviously, because it was my first completed project that I felt sounded like real music. It happened fairly quickly (about two months in 1981) from initial sketches to finished master tapes. The motivation was quite simply to make an LP.

Rimarimba: Chicago Death Excretion Geometry was planned for at least two years and fully scored (subsequently lost). Having entered the score into some MIDI enabled computers linked to synthesizers I pressed ‘play’ and out it came. Satisfying to have set myself the task of building a long piece from fragmented canons but ultimately rather sterile.

More recently, I was very pleased with Rimarimba: Wisdom Of Crowds. A large scale multitracked composition assembled in the studio and first mixed live at Café Oto, London, in 2019. This was my debut live gig and went down well. The piece itself is at least 90% of what I was trying to achieve.

There are many descriptions of the ideal state of mind for being creative. What is it like for you? What supports this ideal state of mind and what are distractions? Are there strategies to enter into this state more easily?

Clear up correspondence and emails, know the allotment doesn’t need attention today, aim to have several hours free and try not to be distracted by anything going on in my life. Most importantly the compositional head of steam has to have built up to a point where it will overwhelm everything else.

Music and sounds can heal, but they can also hurt. Do you personally have experiences with either or both of these? Where do you personally see the biggest need and potential for music as a tool for healing?

I don‘t recall having been hurt by music other than the horror of Christmas songs in shops. As for healing well, on those rare occasions when I feel a bit down, Toumani Diabate & Ballake Sissoko’s New Ancient Strings is always a life affirming listen [Read our Ballake Sissoko interview], as is Dan Hicks And His Hot Licks: Striking It Rich. The latter is probably the most unashamedly joyous music I have encountered to date.

There is a fine line between cultural exchange and appropriation. What are your thoughts on the limits of copying, using cultural signs and symbols and the cultural/social/gender specificity of art?

Cultural exchange is a lifeblood of the arts in general and music in particular. Appropriation and misogyny are another matter altogether. I am old enough to remember The Black And White Minstrel Show on UK television (white people performing alongside other white people with black face makeup), Pans People on Top Of The Pops (a scantily clad female dance troupe), Rock against Sexism, Rock against Racism and can’t but help compare that past to the present. Clearly there is a cultural arc that can be followed from the 1960s to 2020s.

Have many wrongs been recognised and attempts to right them been made? Yes, obviously. Are we in danger of becoming a society where being offended on someone else’s behalf has become a form of virtue signalling? I believe we are. The fine line is between taking the time and effort to understand other people and their culture and deciding, without having done so or because this week’s opinionista says so, that we (invariably a white we) know best. This looks and feels a lot like cultural imperialism to me or, if you prefer, a woke version of the noblesse oblige and noble savage concepts of earlier times.

Our sense of hearing shares intriguing connections to other senses. From your experience, what are some of the most inspiring overlaps between different senses - and what do they tell us about the way our senses work?

King Crimson’s Red is amongst the angriest works I know of. It isn’t called Blue or Green. Miles Davis’ Kind Of Blue is the exact opposite. It isn’t titled Kind Of Red either.

But, back to the previous question; my answer is governed by the society and culture I live in. Other people’s answers may well be very different. Our senses work in concert with each other but does anyone really know what goes on in our best friend’s head let alone a complete stranger in a different place or time?

Art can be a purpose in its own right, but it can also directly feed back into everyday life, take on a social and political role and lead to more engagement. Can you describe your approach to art and being an artist?

I have no message to impart. I compose and record because I feel the need to do so and if someone, somewhere, is entertained by what I do that is a bonus.

What can music express about life and death which words alone may not?

Emotion, entirely personal and not corralled by an author’s use of language.

Interviews / About

Fifteen Questions Interview with Robert Cox of Rimarimba and The Same

Make Noise, Mutate Music

"I have always wanted to know and see how things work. A rack of sound processors and synthesizers are much more satisfying to work with than composing software on a computer. Opening up and modifying devices is an inherent part of music production for me."